Melatonin is often described as the body’s “sleep hormone,” and for many people, it’s the first supplement they try when sleep becomes inconsistent. At first, it may seem helpful—falling asleep feels easier, bedtime feels calmer, and nights feel more predictable.

But over time, this effect can fade.

The same dose no longer works. Falling asleep becomes harder again. Nighttime awakenings return. Some people even report feeling worse—groggy in the morning, wired at night, or dependent on taking more melatonin just to feel tired.

This experience is common, and it raises an important question:

Why does melatonin stop working for so many people?

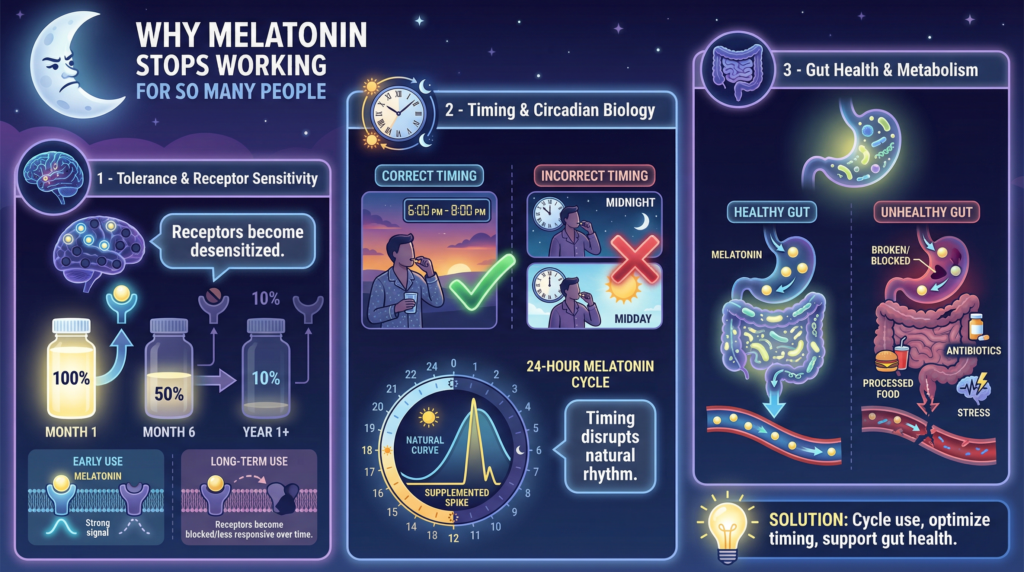

The answer lies in three interconnected factors that are rarely discussed together:

- Tolerance and receptor sensitivity

- Timing and circadian biology

- Gut health and melatonin metabolism

Understanding these mechanisms can help explain not only why melatonin eventually fails, but also why simply increasing the dose often backfires.

Watch Before You Read: Many people rely on over-the-counter or natural sleep aids — but most don’t realize why they eventually stop working. This quick video breaks down the biological and psychological reasons behind tolerance and dependency, plus the evidence-backed methods to restore your sleep rhythm safely.

Over time, many people notice their favorite sleep aids — from melatonin gummies to herbal blends — simply stop helping. This happens because the body can develop tolerance to certain ingredients, especially when used daily. Your brain’s natural production of sleep hormones like melatonin and GABA can also slow down when artificial support is overused.

In this video, we explain why sleep aids stop working, how your circadian rhythm adapts, and the science-backed steps you can take to reset your natural sleep cycle. You’ll also learn which non-habit-forming, herbal sleep aids can restore long-term balance without dependency or next-day grogginess.

🌿 Ready to get back to deep, natural sleep — without relying on heavy sleep aids?👉 Discover Yusleep – a balanced, herbal formula designed to support your body’s natural sleep rhythm and break the dependency cycle.

Melatonin Is a Signal—Not a Sedative

One of the biggest misconceptions about melatonin is that it “puts you to sleep.”

In reality, melatonin functions as a timing signal, not a knockout agent. It tells the brain that darkness has arrived and that it’s time to initiate sleep-related processes. It does not directly cause sleep in the way sedatives do.

Melatonin:

- It is released by the pineal gland in response to darkness.

- Helps coordinate circadian rhythms

- Signals the body to prepare for sleep

- Works in coordination with serotonin, cortisol, and core body temperature

When melatonin is taken as a supplement, it adds an external signal to this system. When used occasionally and at the right time, this can be helpful. When used nightly or at high doses, problems can emerge. When melatonin stops working, the issue is rarely the supplement itself. Sleep regulation depends on interconnected systems involving gut bacteria, neurotransmitters, inflammation, and circadian rhythm.

To understand how these systems interact—and why sleep problems often persist even with “perfect” timing—it helps to look at the broader picture.

⭐Read the complete guide to gut health and sleep regulation

Melatonin Tolerance: What’s Really Happening

Does the Body Become “Dependent” on Melatonin?

Melatonin is not classified as addictive in the conventional sense. Nevertheless, regular supplementation can modify the body’s responsiveness to melatonin signaling. To help you gauge whether this might be happening to you, consider these questions: Have you needed to double your dose lately to achieve the same effect?

Do you find that you are taking melatonin more frequently than before? Reflecting on these can help you better understand your own tolerance levels.

Research suggests that repeated exposure to elevated melatonin levels may lead to:

- Reduced sensitivity of melatonin receptors (MT1 and MT2)

- Disruption of the body’s natural melatonin rhythm

- A blunted response to both endogenous and supplemental melatonin

In simple terms, the brain may start to ignore the signal.

This is similar to how repeatedly snoozing an alarm eventually makes it less effective.

Why Higher Doses Often Make Things Worse

Many over-the-counter melatonin supplements contain dosages that are significantly higher than endogenous production. While physiological nighttime melatonin levels are measured in micrograms, commercial supplements frequently provide 3 to 10 milligrams or more.

High doses can:

- Overstimulate melatonin receptors

- Shift circadian timing incorrectly.

- Increase next-day grogginess

- Suppress the body’s own melatonin production.

Instead of improving sleep quality, higher doses may fragment sleep and worsen timing issues.

Timing Matters More Than Dose

Melatonin and the Circadian Clock

Melatonin works in close coordination with the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN)—the brain’s master clock. This system is exquisitely sensitive to timing.

Taking melatonin too late, too early, or inconsistently can:

- Shift the circadian rhythm in the wrong direction.

- Delay sleep onset rather than improve it.

- Create a mismatch between sleep pressure and sleep timing.

This is why melatonin may initially help with jet lag or schedule changes, but fail when used nightly without attention to timing.

The Light–Melatonin Conflict

Artificial light—especially blue light—suppresses melatonin production. Taking melatonin while continuing late-night screen use sends conflicting signals to the brain:

- Supplemental melatonin says “night.”

- Light exposure says “day.”

Over time, this conflict weakens the effectiveness of melatonin supplementation and further disrupts the circadian rhythm.

The Gut’s Role in Melatonin Metabolism (Often Overlooked)

One of the most surprising findings in sleep research is that the majority of the body’s melatonin is produced in the gut, not the brain.

Enterochromaffin cells in the gastrointestinal tract produce melatonin in quantities far exceeding pineal production. While gut-derived melatonin does not directly regulate sleep timing, it plays a critical role in:

- Circadian signaling

- Immune regulation

- Inflammation control

- Gut–brain communication

Gut Bacteria and Melatonin Pathways

The gut microbiome influences melatonin in several ways:

- Modulating tryptophan availability

- Influencing serotonin production (melatonin’s precursor)

- Affecting inflammation that interferes with sleep signaling

- Regulating intestinal permeability, which impacts circadian stability

Disruptions in gut health, such as dysbiosis, low microbial diversity, or chronic inflammation, can impair melatonin signaling even when supplements are used. To support microbiome balance, consider incorporating simple actions into your daily routine.

For example, adding prebiotic fiber to your breakfast can be an easy way to start nurturing your gut health. This small step can contribute to a more robust and diverse gut microbiota, potentially enhancing melatonin signaling and overall sleep quality.

When Melatonin Backfires

For some individuals, melatonin supplementation may lead to:

- Vivid dreams or nightmares

- Increased nighttime awakenings

- Morning fatigue

- Mood changes

- A sense of being “wired but tired.”

These effects are not necessarily side effects in the traditional sense—they are often signs that circadian timing or underlying biology is being disrupted rather than supported.

Why Melatonin Isn’t a Long-Term Sleep Strategy

Melatonin can be useful in specific situations:

- Short-term jet lag

- Temporary schedule shifts

- Delayed sleep phase syndrome (with proper timing)

However, it is not designed to:

- Override chronic stress

- Correct gut dysbiosis

- Replace consistent sleep routines.

- Act as a nightly sedative

When used long-term without addressing underlying factors, melatonin often loses effectiveness. If a pill hasn’t fixed sleep in six months, what root cause might still be unaddressed? Inviting this reflection can support a deeper understanding of one’s sleep issues without relying solely on supplementation.

A More Sustainable Way to Support Sleep

Sleep is an emergent property of multiple systems working together:

- Circadian rhythm

- Neurotransmitters (serotonin, GABA)

- Stress hormones (cortisol)

- Gut health and inflammation

- Light exposure and behavior

This is why many people eventually move away from single-hormone solutions and toward upstream approaches that support sleep.

Supporting calm, rhythm, and biological timing often produces more durable improvements than forcing sleep with a single compound.

If you’re exhausted but feel wired at night, stress hormones—not sleep effort—may be the missing piece. We analyzed Yu Sleep through the lens of cortisol regulation, circadian rhythm, and real-world recovery data.

Frequently Asked Questions

Does melatonin stop working for everyone?

No. Some people continue to benefit from occasional, low-dose use. Problems are more common with nightly, high-dose supplementation.

Is melatonin safe long-term?

Melatonin is generally considered safe for short-term use. Long-term nightly use is still being studied, especially at higher doses.

Are there supplements that support sleep without acting as sedatives?

Yes. Some supplements are formulated to support calm, sleep signaling, and circadian rhythm rather than forcing sedation.

We reviewed one such option here.

Can gut health really affect melatonin?

Yes. The gut produces large amounts of melatonin and influences serotonin metabolism, inflammation, and circadian signaling.

Why do I feel groggy after taking melatonin?

Grogginess is often dose-related or timing-related. High doses or late-night use can disrupt circadian alignment.

What’s the alternative if melatonin doesn’t work anymore?

Many people focus on supporting relaxation, circadian rhythm, stress regulation, and gut health rather than directly supplementing melatonin.

Final Thoughts: Melatonin Isn’t Broken—The Context Is

Melatonin doesn’t usually “stop working” because the hormone itself is flawed. It stops working because sleep is more complex than a single signal.

Tolerance, mistimed use, light exposure, stress, and gut health all shape how melatonin functions. Without addressing these factors, increasing the dose rarely leads to better sleep—and often makes things worse.

Understanding why melatonin fails is the first step toward building a more effective, sustainable sleep strategy.

Melatonin as a Timing Signal, Not a Sedative

Many clinical reviews note that melatonin’s role in humans primarily involves phase-shifting circadian rhythms and helping align sleep timing with natural light-dark cycles, rather than acting as a standalone sedative. Low, physiologic doses taken at the right time can improve sleep onset and circadian synchronization. PubMed+1

Tolerance and Receptor Sensitivity

Research on melatonin receptors (MT1 and MT2) shows these receptors are highly concentrated in the brain’s circadian center (the suprachiasmatic nucleus) and that their responsiveness influences how melatonin signals the body to initiate sleep. Chronic high exposure can blunt sensitivity, affecting effectiveness over time. PubMed

Timing and Early Circadian Signaling

Melatonin’s effectiveness depends heavily on the timing of administration relative to an individual’s biological night — its secretion is controlled by the circadian clock (suprachiasmatic nucleus) and peaks at night to encourage the transition from wake to sleep. PubMed

Light Exposure and Melatonin Suppression

Light exposure, especially blue-rich light at night, suppresses endogenous melatonin. This conflict between light signals and supplemental melatonin can weaken its signaling over time. PubMed

Gut Microbiome and Melatonin

Emerging research shows that melatonin interacts with the gut microbiota, influencing microbial rhythms and recovery from sleep restriction. For instance, exogenous melatonin can help restore the disrupted circadian rhythmicity of gut microbes after sleep loss. PubMed

Additionally, studies indicate that melatonin’s neuroprotective effects in sleep-deprived animals involve changes in gut bacterial populations and metabolites, suggesting a microbiota–gut–brain interaction with sleep hormones. SpringerLink