Many sleep problems do not result from a lack of sleep aids but rather from a misaligned biological clock.

Common experiences reported by individuals include the following:

- Feeling tired all day but wired at night

- Falling asleep late despite exhaustion

- Waking up frequently or too early

- Feeling “off” even after enough hours in bed

These patterns are hallmarks of circadian rhythm disruption, a condition increasingly common in modern environments.

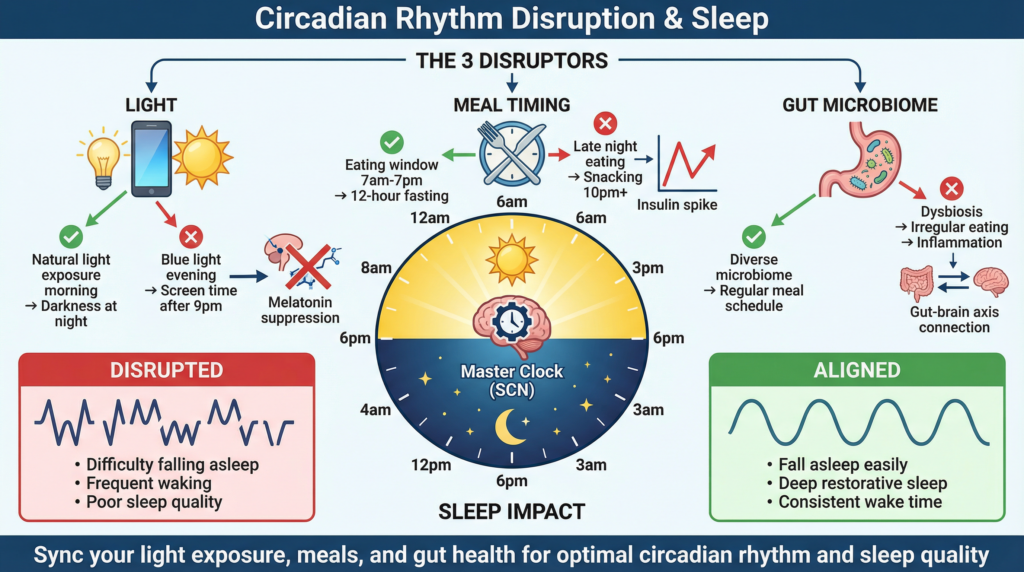

To understand why sleep becomes inconsistent, fragmented, or unrefreshing, it helps to look beyond individual hormones and examine the circadian system as a whole, including light exposure, meal timing, and the gut microbiome. These factors can be illustrated through a fictional character, Alex, whose experience links the concepts discussed.

Each morning, Alex opens the blinds to soak up the early sunlight, setting the stage for their daily rhythm. However, late-night work pushes Alex’s dinner well past the normal time, introducing irregular meal cues that disrupt their metabolic rhythm.

As Alex navigates the day, their gut microbiome reacts to these shifts, further influencing how refreshed they feel after a night’s sleep. Through Alex’s journey, the intricate interplay of these factors unfolds, offering a relatable glimpse into the science behind sleep.

What Is Circadian Rhythm Disruption and Why It Affects Sleep

The circadian rhythm is a roughly 24-hour biological cycle that regulates:

- Sleep–wake timing

- Hormone release (melatonin, cortisol)

- Body temperature

- Metabolism

- Immune function

At the center of this system is the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN). The SCN is a small group of nerve cells in the hypothalamus, a part of the brain, and acts as the body’s master clock.

This master clock does not work on its own. It uses outside cues from the environment, called zeitgebers (from German, meaning “time givers”), to stay in sync. Common zeitgebers include light, meal timing, and activity. Circadian rhythm disruption rarely occurs in isolation. Research increasingly shows that sleep timing, neurotransmitters, and the gut microbiome interact through the gut–brain axis and sleep regulation, influencing how well the body transitions into restorative sleep.

The strongest of these cues is:

- Light

- Food timing

- Activity and rest cycles

When these cues become inconsistent, sleep quality often deteriorates — even if total sleep time appears adequate.

Light: The Primary Driver of Circadian Timing. Building on the overview of external cues, let’s focus on light, the most influential factor affecting circadian rhythm.

Light exposure directly influences the SCN via specialized photoreceptors in the retina. Morning light reinforces daytime alertness, while darkness triggers the release of melatonin.

Problems arise when light exposure is mistimed.

Nighttime exposure to artificial light — especially blue-wavelength light — can:

- Suppress melatonin production

- Delay the circadian phase.

- Reduce sleep pressure

- Fragmented sleep architecture

This is why many people find that melatonin supplements stop working if late-night screen exposure continues unchecked.

Morning Light vs. Evening Light

Circadian biology is asymmetric:

- Morning light strengthens rhythm and advances sleep timing.

- Evening light delays rhythm and pushes sleep later.

Without sufficient morning light, the circadian system becomes weaker and more vulnerable to disruption later in the day.

Meal Timing: An Overlooked Circadian Signal

While light sets the master clock, food timing sets peripheral clocks throughout the body — particularly in the liver and gut.

Eating late at night can:

- Shift metabolic rhythms

- Delay melatonin secretion

- Increase nighttime body temperature.

- Interfere with sleep onset.

Research shows that irregular meal timing, such as meals drifting by more than two hours from a regular schedule, can desynchronize peripheral clocks from the central clock. This desynchronization can lead to internal misalignment even when sleep duration remains unchanged.

Late Eating and Sleep Fragmentation

Late-night eating is associated with:

- Reduced slow-wave sleep

- Increased nighttime awakenings

- Lower sleep efficiency

This may explain why some people feel restless at night despite being physically tired.

The Gut Microbiome Runs on a Clock Too

The gut microbiome is not static; it follows diurnal rhythms that fluctuate across the day and night. Picture the microbes as nocturnal janitors and daytime chefs, seamlessly orchestrating a balance that influences our health. These microbes exhibit predictable daily oscillations, interact with host circadian genes, and influence inflammation and neurotransmitter production.

Healthy gut bacteria:

- Exhibit predictable daily oscillations.

- Interact with host circadian genes.

- Influence inflammation and neurotransmitter production.

Circadian disruption alters microbial composition, reducing diversity and impairing rhythmic signaling between the gut and brain.

Gut Dysbiosis and Circadian Misalignment

Disrupted sleep or irregular schedules can:

- Reduce beneficial microbial rhythms.

- Increase inflammatory signaling

- Change the way the body handles the brain chemicals serotonin and melatonin, which help control mood and sleep.

- Reinforce sleep fragmentation

This creates a feedback loop: Poor sleep disrupts the gut → disrupted gut worsens sleep.

This loop explains why addressing circadian rhythm alone — without considering gut health — often produces incomplete results.

Shift Work, Travel, and “Social Jet Lag”

Circadian disruption isn’t limited to night shift workers.

Many people experience social jet lag, where:

- Weekday and weekend schedules differ significantly.

- Bedtimes shift later on days off.

- Light and meal timing become inconsistent.

Even small but repeated shifts can weaken circadian stability over time.

Why Sleep Aids Often Fail in Circadian Disruption

When sleep problems are driven by circadian misalignment:

- Sedatives may induce unconsciousness without restoring rhythm.

- Melatonin may shift timing incorrectly if mistimed.

- Increasing dosage rarely fixes the underlying issue.

This is why many people describe sleep aids as working initially, then losing effectiveness.

Restoring Circadian Alignment: Foundational Strategies

Circadian health is built on consistency, not force. To support and align your body’s internal clocks, consider implementing a simple morning ritual:

– Wake up and open the blinds to let in natural light.

– Sip a glass of water to hydrate.

– Step outside for a few minutes to receive direct sunlight.

In addition to a morning routine, consider establishing an evening routine that prepares your body for restful sleep. Dimming the lights at least an hour before bed can signal your brain to begin producing melatonin. Incorporating relaxing activities such as reading or gentle stretching helps ease the transition to sleep.

For meal timing, aim to have your last meal at least two to three hours before bed. This can prevent late-night eating from affecting your sleep quality. Eating earlier aligns with your body’s natural rhythms and can help regulate body temperature and metabolic processes.

Managing light at night is also crucial. Limiting screen time and using blue-light-filtered devices can reduce exposure that may keep you awake. Instead, use warmer evening lighting to mimic natural sunset cues.t

These steps translate principles into action, encouraging a routine that supports circadian health.

Key principles include:

- Morning light exposure within 30–60 minutes of waking

- Dimming lights in the evening

- Consistent meal timing

- Avoiding late-night heavy meals

- Maintaining regular sleep and wake times

Supporting the circadian system upstream often improves sleep quality more sustainably than targeting sleep directly.

Where Sleep Support Fits In

For individuals whose circadian rhythm is weakened by stress, lifestyle, or long-term disruption, some choose to explore non-sedative sleep support tools that align with calm and rhythm rather than forcing sleep.

When circadian rhythm disruption persists despite lifestyle adjustments, some people explore non-sedative sleep support options designed to work with the body’s natural timing rather than override it.

One such option is Yu Sleep, which focuses on calming the nervous system and supporting sleep architecture without relying on melatonin or habit-forming compounds.👉 Read our science-based review of Yu Sleep here

Frequently Asked Questions

Can circadian rhythm disruption cause insomnia?

Yes. Misalignment between internal clocks and external cues often leads to difficulty falling asleep, staying asleep, or waking refreshed.

Does eating late really affect sleep?

Yes. Late meals can delay circadian signaling and interfere with melatonin release.

Is gut health linked to circadian rhythm?

Yes. Gut microbes follow daily rhythms and influence sleep-related neurotransmitters and inflammation.

Why do weekends ruin my sleep schedule?

Large differences between weekday and weekend sleep timing can lead to repeated circadian shifts, similar to jet lag.

Can supplements fix circadian rhythm issues?

Supplements alone rarely fix rhythm disruption. They work best when paired with light, timing, and behavioral consistency.

Final Thoughts: Sleep Is a Timing Problem More Than a Willpower Problem

Circadian rhythm disruption explains why sleep issues are so persistent — and why quick fixes rarely last.

Sleep improves most reliably when the body’s internal clocks are supported rather than overridden. Light exposure, meal timing, and gut health all play critical roles in maintaining that alignment.

Understanding this system helps explain why non-sedative, rhythm-supportive approaches are increasingly explored by people seeking sustainable sleep improvement. A practical starting point is to track your sleep patterns and light exposure for a week. This simple step empowers you to identify areas for improvement and begin making effective changes right away.

For readers whose sleep issues stem from chronic circadian disruption, stress, or nervous system overactivation, solutions that emphasize rhythm and recovery may be more effective than traditional sleep aids.

We reviewed Yu Sleep through the lens of neuroscience and circadian biology, including real-world recovery data and user-reported outcomes.

Circadian Rhythm & the Suprachiasmatic Nucleus

The suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) functions as the body’s master circadian clock, coordinating sleep–wake cycles, hormone secretion, metabolism, and body temperature in response to environmental cues, particularly light.

Citation:

Reppert SM, Weaver DR. Coordination of circadian timing in mammals. Nature. 2002.

NIH PubMed: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11805865/

Light Exposure and Melatonin Suppression

Evening exposure to artificial and blue-wavelength light suppresses endogenous melatonin production, delays circadian phase, and disrupts sleep onset and architecture. This means that your 10 p.m. Netflix session can stall melatonin production in the same way as exposure to bright lights during the evening.

Citation:

Cajochen C, et al. Evening exposure to blue light stimulates cognitive activity in the brain. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011.

NIH PubMed: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21193540/

Meal Timing as a Circadian Zeitgeber

Food timing acts as a powerful circadian cue for peripheral clocks, particularly in metabolic tissues, and misaligned eating schedules can desynchronize internal rhythms from the central clock.

Citation:

Panda S. Circadian physiology of metabolism. Science. 2016.

NIH PubMed: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26912894/

Late Eating and Sleep Quality

Late-night eating has been associated with reduced sleep efficiency, delayed melatonin onset, and increased nighttime awakenings.

Citation:

Spaeth AM, et al. Effects of experimental sleep restriction on weight gain, caloric intake, and meal timing. Sleep. 2013.

NIH PubMed: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23429386/

Gut Microbiome and Circadian Rhythms

The gut microbiome exhibits diurnal oscillations that interact with host circadian genes. Circadian disruption alters microbial composition and increases inflammatory signaling that can impair sleep regulation. What if your late snack is talking to your clock through bacteria, influencing your sleep in ways you never imagined?

Citation:

Thaiss CA, et al. Transkingdom control of microbiota diurnal oscillations promotes metabolic homeostasis. Cell. 2014.

NIH PubMed: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25259949/

Sleep Loss, Gut Dysbiosis, and Feedback Loops

Sleep disruption can induce gut dysbiosis, which in turn worsens circadian misalignment through inflammatory and neurotransmitter pathways, creating a self-reinforcing loop.

Citation:

Benedict C, et al. Gut microbiota and sleep. Trends Mol Med. 2017.

NIH PubMed: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28442210/

Why Sleep Aids Fail in Circadian Disruption

Sedative approaches may induce sleep without restoring circadian alignment, resulting in fragmented sleep and reduced long-term effectiveness.

Citation:

Zisapel N. Melatonin and sleep disorders. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2009.

NIH PubMed: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19594453/

Your circadian rhythm responds to signals — not willpower.

Light exposure, meal timing, and gut health quietly shape when your body feels alert or ready for sleep. When those signals are misaligned, sleep becomes lighter, fragmented, and harder to sustain. To learn how to restore circadian alignment, calm the nervous system, and support deeper, more consistent sleep naturally.