Introduction: Why Sleep Hormones Are No Longer Just “Brain Chemicals”

Have you ever wondered why sleep feels so elusive, even when you follow all the classic advice? For decades, sleep science told us to look only to the brain. Experts insisted serotonin and melatonin were purely brain chemicals, influenced by light and neural activity. But in the last 15–20 years, a new story has begun to unfold—one that challenges this view.

Today, we know an entire ecosystem is at play. The gut microbiome—home to trillions of bacteria—doesn’t just quietly digest your food. These microbes help orchestrate your sleep by influencing how your body makes, transforms, and senses serotonin and melatonin. Through hidden metabolic, immune, and neural pathways, gut microbes affect the very rhythms that help you drift off at night and wake refreshed.

This scientific frontier is where microbiology, neurobiology, endocrinology, and circadian research collide. Imagine all those fields working together to reveal how a bustling world in your gut shapes your every night’s sleep. How exactly do these gut microbes link to serotonin and melatonin levels? Let’s dive into these key pathways and unlock their secrets.

Pull Quote:

“The gut is not just a passive digestive organ — it is a neurochemical factory with direct influence over sleep-regulating hormones.”

This article examines interactions among gut bacteria, serotonin, and melatonin, citing animal and human studies, including research indexed by Stanford Medicine and the NIH.

Want the complete picture of how gut health impacts sleep? Explore our in-depth pillar guide on the microbiome, insomnia, and evidence-based ways to support better sleep naturally.

The Biochemical Foundation: Tryptophan, Serotonin, and Melatonin

The Core Pathway

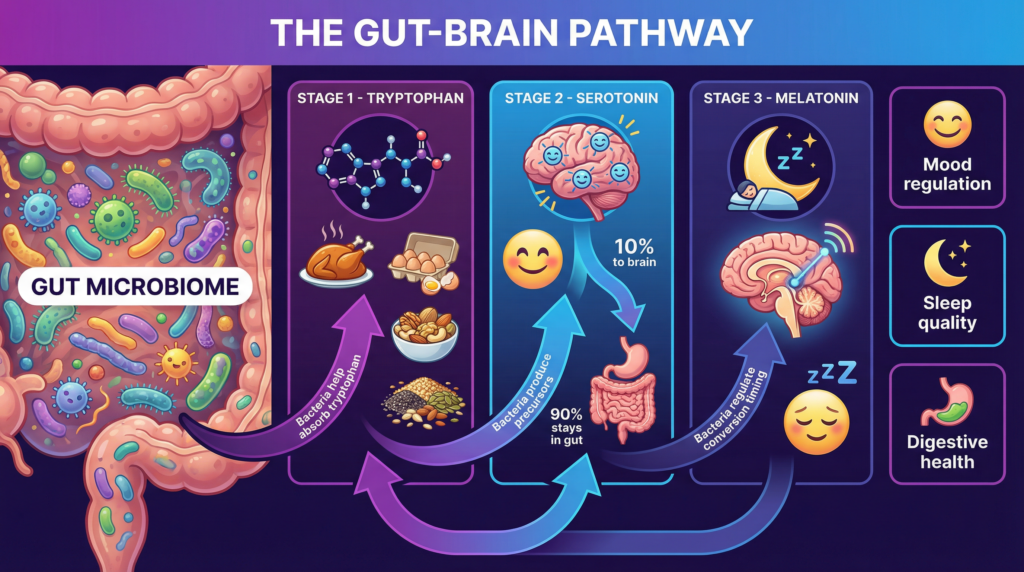

At the center of sleep hormone biology is a simple but powerful biochemical cascade:

- → Tryptophan (an essential dietary amino acid)

- → Serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine)

- → Melatonin

Tryptophan must be obtained from food. Once absorbed, it can follow multiple metabolic pathways, including:

- Conversion into serotonin

- Diversion into kynurenine metabolites

- Transformation into microbial indoles

Serotonin serves dual roles:

- In the brain: regulating mood, arousal, and wakefulness

- In the periphery: controlling gut motility and immune signaling

Melatonin, synthesized primarily from serotonin in the pineal gland, acts as the body’s biological night signal, synchronizing circadian rhythms and sleep timing.

Crucially, gut bacteria influence the amount of tryptophan that enters each pathway (Agus et al., 2018).

How Gut Bacteria Regulate Serotonin

With the basics in place, you might be asking: how do these tiny gut residents actually take control of serotonin—one of your body’s most important chemicals?

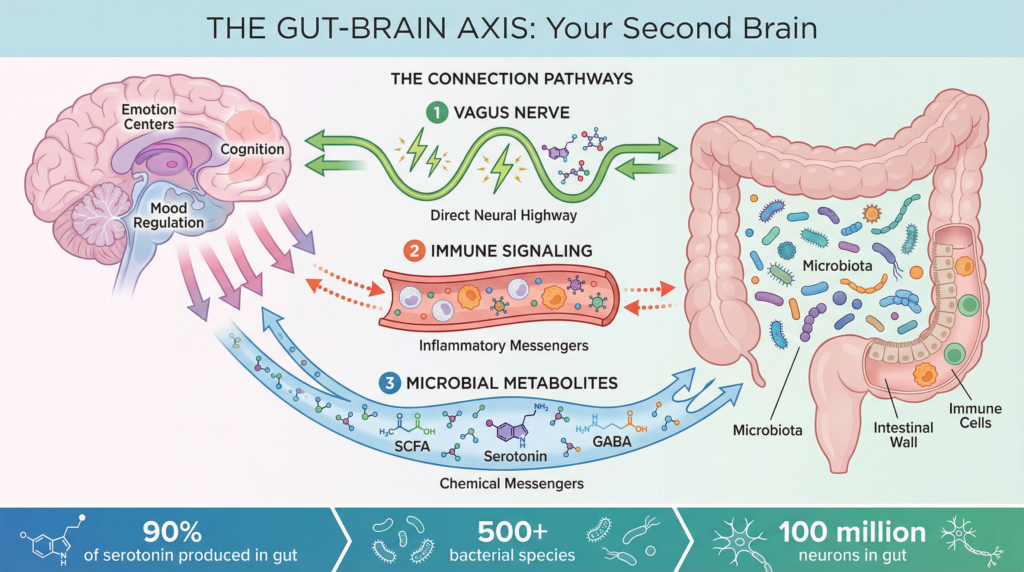

Approximately 90–95% of the body’s serotonin is produced in the gastrointestinal tract, not the brain (Yano et al., 2015).

Specialized gut cells called enterochromaffin cells synthesize serotonin in response to:

- Mechanical stimulation

- Nutrients

- Microbial metabolites

Microbial Control of Serotonin Production

Groundbreaking NIH-indexed research demonstrated that:

- Germ-free mice produce significantly less serotonin.

- Colonization with specific gut bacteria restores serotonin levels.

Yano et al. (2015) identified spore-forming bacteria that stimulate host serotonin biosynthesis via microbial metabolites, including short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs).

Pull Quote:

“Certain gut bacteria directly stimulate host serotonin production, effectively acting as endocrine regulators.”

Although peripheral serotonin does not freely cross the blood–brain barrier, it influences sleep indirectly via:

- Vagal nerve signaling

- Immune modulation

- Precursor availability for central serotonin synthesis

This is part of a larger sleep–microbiome connection. Read our complete pillar article explaining how gut health influences insomnia, sleep quality, and circadian rhythm.

From Serotonin to Melatonin: Microbial Influence on Circadian Timing

Melatonin Is Not Only Made in the Brain

While the pineal gland is the primary source of circulating melatonin, melatonin is also synthesized in the gastrointestinal tract, often at concentrations far exceeding those in blood plasma (Bubenik, 2002).

Emerging evidence suggests:

- Gut tissues express melatonin-synthesizing enzymes.

- Microbial signals influence these enzymes.

- Melatonin in the gut may regulate both intestinal barrier integrity and circadian signaling.

Animal Evidence for Microbial Control of Melatonin

NIH-indexed studies show that:

- Antibiotic depletion of gut bacteria alters melatonin rhythms.

- Fecal microbiota transplantation can restore disrupted circadian patterns.

- Certain Lactobacillus species (types of beneficial gut bacteria) increase host melatonin production.

These findings suggest that microbes shape systemic melatonin signaling rather than merely responding to it.

Stanford Medicine and the Gut–Brain–Sleep Axis

Stanford Medicine researchers emphasize that the gut–brain axis represents a bidirectional communication network involving:

- Neural pathways (vagus nerve)

- Endocrine signaling

- Immune modulation

- Microbial metabolites

Stanford-published summaries highlight that gut microbes influence neurotransmitters, including serotonin, which affects mood, cognition, and sleep regulation (Stanford Medicine, 2025).

Pull Quote:

“Microbes influence the brain through chemical signals, immune pathways, and neural circuits — sleep is one of their downstream effects.”

This institutional framing supports the value and relevance of microbiome-based sleep research.

Sleep Architecture and the Microbiome

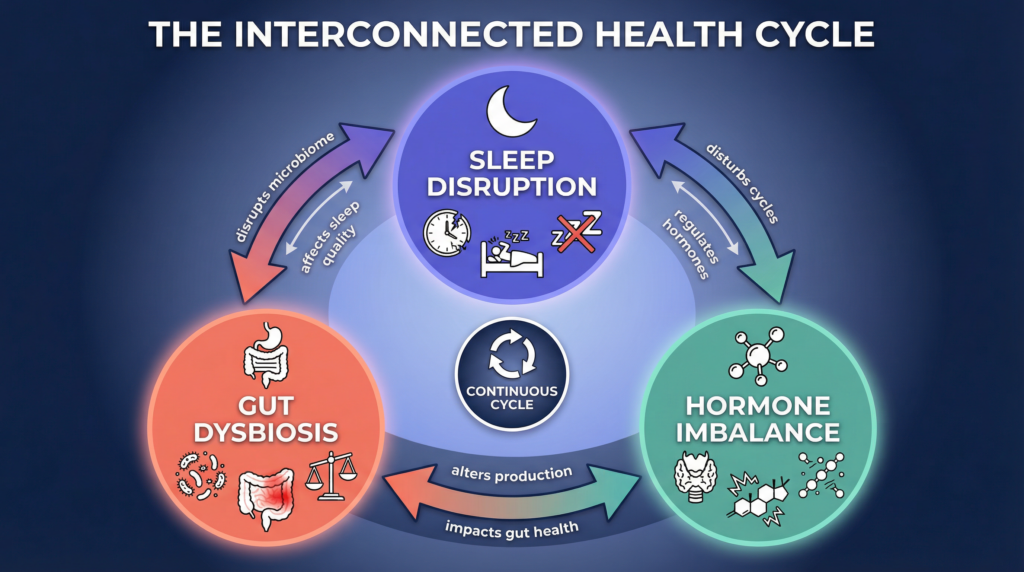

But here’s a twist: it’s not just that microbes influence your sleep. The quality of your sleep can, in turn, reshape your unique community of gut bacteria. Ready to see how this relationship swings both ways?

The relationship is not one-way.

Sleep deprivation:

- Reduces microbial diversity

- Increases pro-inflammatory taxa

- Alters circadian oscillations of gut bacteria

Human actigraphy studies show that sleep fragmentation correlates with reduced microbial richness and altered metabolite profiles (Benedict et al., 2016).

This creates a feedback loop:

- Poor sleep → dysbiosis

- Dysbiosis → impaired serotonin/melatonin signaling

- Impaired signaling → worse sleep

Human Clinical Evidence: What We Know So Far

Observational Studies

Multiple NIH-indexed observational studies report associations between:

- Short sleep duration and altered microbiome composition

- Shift work and disrupted microbial circadian rhythms.

- Insomnia symptoms and reduced SCFA-producing bacteria

While correlational, these findings are consistent across populations.

Interventional Trials

Systematic reviews of randomized controlled trials indicate that:

- Certain probiotics modestly improve subjective sleep quality.

- Prebiotic fibers improve sleep efficiency in some cohorts.

- Effects are strain-specific and dose-dependent (Haarhuis et al., 2022)

Importantly, no evidence suggests dependency or sedation, distinguishing microbiome approaches from pharmacologic sleep aids.

Practical Implications (Evidence-Aligned)

Diet and Microbial Substrates

- Fiber-rich diets support SCFA producers.

- Tryptophan-containing foods provide hormone precursors.

- Polyphenols modulate microbial diversity.

Circadian-Aligned Eating

- Meal timing influences microbial rhythms.

- Late-night eating disrupts melatonin signaling.

Probiotics and Prebiotics

- Should be strain-specific

- Monitored over 6–8 weeks

- Used as adjuncts, not replacements, for CBT-I

👉 Looking for actionable steps to improve sleep through gut health? Our pillar post breaks down diet, lifestyle, and evidence-based strategies that support restorative sleep.

Limitations and Research Gaps

Despite exciting findings:

- Most causal evidence comes from animals.

- Human trials remain heterogeneous.

- Personalized responses vary widely.

Future research priorities include:

- Large RCTs with polysomnography

- Microbiome-guided personalization

- Integrated circadian + microbiome interventions

Conclusion

The relationship between gut bacteria, serotonin, and melatonin regulation represents a paradigm shift in sleep science. The gut microbiome is not merely associated with sleep — it actively shapes the biochemical pathways that govern circadian timing and sleep quality.

Animal models show causality, and human studies report consistent associations. Institutions like Stanford Medicine and NIH-funded researchers are translating this science into clinical practice.

While microbiome-based sleep therapies are still emerging, the evidence strongly supports viewing gut health as a foundational component of sleep hormone regulation — not an afterthought.

Continue the deep dive: Read our comprehensive pillar guide on gut health and sleep to understand how microbiome science translates into better nights.

Frequently Asked Questions

How do gut bacteria affect serotonin and melatonin production?

Gut bacteria influence how dietary tryptophan is metabolized, directing it toward serotonin production or alternative pathways. Certain microbes stimulate gut cells to produce serotonin, which can then be converted into melatonin, helping regulate circadian rhythms and sleep timing.

Is most serotonin really produced in the gut?

Yes. Research shows that approximately 90–95% of the body’s serotonin is produced in the gastrointestinal tract by enterochromaffin cells, not in the brain. Gut microbes play a key role in stimulating this production.

Are there supplements that support sleep without acting as sedatives?

Yes. Some supplements are formulated to support calm, sleep signaling, and circadian rhythm rather than forcing sedation. We reviewed one such option here.

We reviewed one such option here

Can improving gut health help with insomnia?

Improving gut health may help support sleep by stabilizing serotonin and melatonin signaling, reducing inflammation, and supporting circadian rhythm alignment. However, gut-based interventions should be viewed as complementary to proven treatments like cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I).

Do probiotics increase melatonin levels?

Some animal and human studies suggest that specific probiotic strains may influence melatonin production indirectly by altering gut metabolism and circadian signaling. Effects appear to be strain-specific and modest, not sedative.

Does poor sleep damage the gut microbiome?

Yes. Sleep deprivation and irregular sleep schedules can reduce microbial diversity and disrupt normal gut bacterial rhythms, creating a feedback loop that may further impair sleep quality.

Is microbiome-based sleep therapy clinically proven?

Not yet. While animal studies show causal effects and early human trials are promising, microbiome-based sleep therapies are still emerging and not considered first-line clinical treatments for insomnia.

Sleep hormones don’t work in isolation — they depend on gut health and biological timing.

Serotonin production, melatonin release, and circadian rhythm are all shaped by signals coming from the gut. When those signals are disrupted, sleep becomes lighter, shorter, and harder to regulate.

Learn how gut health, inflammation, and circadian alignment work together to restore deep, consistent sleep naturally.

References (APA 7th Edition)

Agus, A., Planchais, J., & Sokol, H. (2018). Gut microbiota regulation of tryptophan metabolism in health and disease. Cell Host & Microbe, 23(6), 716–724.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chom.2018.05.003

Yano, J. M., et al. (2015). Indigenous gut bacteria regulate host serotonin biosynthesis. Cell, 161(2), 264–276.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2015.02.047

Liu, B., et al. (2024). Gut microbiota regulates host melatonin production and circadian rhythm. Frontiers in Endocrinology.

https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2024.1298743

Benedict, C., et al. (2016). Acute sleep deprivation alters the composition of the gut microbiota in humans. Molecular Metabolism, 5(12), 1175–1182.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molmet.2016.10.003

Haarhuis, J. E., et al. (2022). Probiotics, prebiotics, and postbiotics for sleep quality: A systematic review. Nutrients, 14(9), 1907.

https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14091907

Stanford Medicine. (2025). The gut–brain connection: What the science says.

https://news.stanford.edu